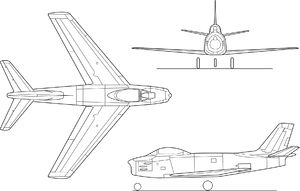

North American F-86 Sabre

| F-86 Sabre | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| A North American F-86 during the Oshkosh Air Show | |

| Role | Fighter aircraft |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | North American Aviation |

| First flight | 1 October 1947 |

| Introduced | 1949, USAF |

| Retired | 1994, Bolivia |

| Primary users | United States Air Force Japanese Air Self-Defense Force Spanish Air Force Republic of Korea Air Force |

| Number built | 9,860 |

| Unit cost | US$219,457 (F-86E)[1] |

| Developed from | FJ-1 Fury |

| Variants | F-86D Sabre Canadair Sabre CAC Sabre FJ-2/-3 Fury |

| Developed into | North American YF-93 |

The North American Aviation F-86 Sabre (sometimes called the Sabrejet) was a transonic jet fighter aircraft. The Sabre is best known for its Korean War role where it was pitted against the Soviet MiG-15. Although developed in the late 1940s and outdated by the end of the 1950s, the Sabre proved adaptable and continued as a front line fighter in air forces until the last active front line examples were retired by the Bolivian Air Force in 1994.

Its success led to an extended production run of more than 7,800 aircraft between 1949 and 1956, in the United States, Japan and Italy. It was by far the most-produced Western jet fighter, with total production of all variants at 9,860 units.[2]

Variants were built in Canada and Australia. The Canadair Sabre added another 1,815 airframes, and the significantly redesigned CAC Sabre (sometimes known as the Avon Sabre or CAC CA-27), had a production run of 112.

Contents |

Design and development

Initial proposals to meet a USAAF requirement for a single-seat high-altitude day fighter aircraft/escort fighter/fighter bomber were made in late 1944, and were originally to be derived from the design of the straight wing FJ-1 Fury being developed for the U.S. Navy.[3] The North American P-86 Sabre was the first American aircraft to take advantage of flight research data seized from the German aerodynamicists at the end of the war.[4] Performance requirements were met by incorporating a 35 degree swept-back wing with automatic slats into the design, using the Me 262 wing profile, Messerschmitt wing A layout and adjustable stabilizer.[5][6] Manufacturing was not begun until after World War II as a result. The XP-86 prototype, which would become the F-86 Sabre, first flew on 1 October 1947[7] from Muroc Dry Lake, California.[4]

The USAF Strategic Air Command had F-86 Sabres in service from 1949 through 1950. The F-86s were assigned to the 22nd Bomb Wing, the 1st Fighter Wing and the 1st Fighter Interceptor Wing.[8]

The F-86 was produced as both a fighter-interceptor and fighter-bomber. Several variants were introduced over its production life, with improvements and different armament implemented (see below). The XP-86 (eXperimental Pursuit) was fitted with a General Electric J35-C-3 jet engine that produced 4,000 lbf (18 kN) of thrust. This engine was built by GM's Chevrolet division until production was turned over to Allison.[9] The General Electric J47-GE-7 engine was used in the F-86A-1 producing a thrust of 5,200 lbf (23 kN) while the General Electric J73-GE-3 engine of the F-86H produced 9,250 lbf (41 kN) of thrust.[10] The F-86 was the primary U.S. air combat fighter during the Korean War, with significant numbers of the first three production models seeing combat.

The fighter-bomber version (F-86H) could carry up to 2,000 lb (907 kg) of bombs, including an external fuel-type tank that could carry napalm.[11]

Both the interceptor and fighter-bomber versions carried six 0.50 in (12.7 mm) M3 Browning machine guns with electrically-boosted feed in the nose (later versions of the F-86H carried four 20 mm (0.79 in) cannons instead of machine guns). Firing at a rate of 1,200 rounds per minute each, the .50 in (12.7 mm) guns were harmonized to converge at 1,000 ft (300 m) in front of the aircraft, using armor-piercing (AP) and armor-piercing incendiary (API) rounds, with one armor-piercing incendiary tracer (APIT) for every five AP or API rounds. The API rounds used during the Korean War contained magnesium, which were designed to ignite upon impact but burned poorly above 35,000 ft (11,000 m) as oxygen levels were insufficient to sustain combustion at that height. Initially fitted with the Mark 18 manual-ranging computing gun sight, later models used the A-1CM radar ranging gunsight which used radar to compute the range of a target. This would later prove to be a significant advantage against MiG opponents over Korea, and fitted to later supersonic fighters such as the F-100 Super Sabre and the F-105 Thunderchief.

Unguided 2.75 in (70 mm) rockets were used on some of the fighters on training missions, but 5 inch (127 mm) rockets were later carried on combat operations. The F-86 could also be fitted with a pair of external jettisonable jet fuel tanks (four on the F-86F beginning in 1953) that extended the range of the aircraft.

The F-86 Sabre was also produced under license by Canadair, Ltd., in the Province of Quebec as the Canadair Sabre. The final variant of the Canadian Sabre, the Mark 6, is generally rated as having the highest capablities of any Sabre version made anywhere.[12] The last Sabre to be manufactured by Canadair (Sabre #1815) is now kept in the Western Canada Aviation Museum (WCAM)'s permanent collection in Winnipeg, Manitoba, after being donated by the Pakistan Air Force.[13]

Breaking sound barrier and other records

The F-86A set its first official world speed record of 570 m.p.h. in September 1948.[14]

Several people involved with the development of the F-86, including the chief aerodynamicist for the project and one of its other test pilots, claimed that North American test pilot George Welch had broken the sound barrier in a dive with the XP-86 while on a test flight 1 October 1947.[15] Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier on 14 October 1947 in the rocket-propelled Bell X-1, thus flying first aircraft to sustain supersonic speed in level flight, making it the first "true" supersonic aircraft).[16]

On 18 May 1953, Jacqueline Cochran flying a Canadian-built F-86E alongside Chuck Yeager became the first woman to break the sound barrier.[1] It is unclear whether this was in level flight or not.

Operational history

Korean War

The F-86 entered service with the United States Air Force in 1949, joining the 1st Fighter Wing's 94th Fighter Squadron "Hat-in-the-Ring" and became the primary air-to-air jet fighter used in the Korean War. With the introduction of the Soviet Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 into air combat in November 1950, which outperformed all aircraft then assigned to the United Nations, three squadrons of F-86s were rushed to the Far East in December.[17] Early variants of the F-86 could not outturn, but they could outdive the MiG-15, and the MiG-15 was superior to the early F-86 models in ceiling, acceleration, rate of climb, and zoom. With the introduction of the F-86F in 1953, the two aircraft were more closely matched, with many combat-experienced pilots claiming a marginal superiority for the F-86F. MiGs flown from bases in Manchuria by Red Chinese, North Korean, and Soviet VVS pilots were pitted against two squadrons of the 4th Fighter-Interceptor Wing forward-based at K-14, Kimpo, Korea.[17]

.jpg)

Many of the American pilots were experienced World War II veterans, while the North Koreans and the Chinese lacked combat experience, thus accounting for much of the F-86's success.[18] However, whatever the actual results may have been, it is clear that the F-86 pilots did not experience definitive superiority over the World-War-II-experienced, Soviet-piloted MiG-15s in Korean airspace. According to former communist sources, Soviets initially piloted the majority of MiG-15s that fought in Korea. Later in the war, North Korean and Chinese pilots increased their activity.[19][20] The North Koreans and their allies periodically contested air superiority in MiG Alley, an area near the mouth of the Yalu River (the boundary between Korea and China) over which the most intense air-to-air combat took place. The F-86E's all-moving tailplane has been credited with giving the Sabre an important advantage over the MiG-15. Far greater emphasis has been given to the training, aggressiveness and experience of the F-86 pilots.[18] American Sabre pilots were trained at Nellis, where the casualty rate of their training was so high they were told, "If you ever see the flag at full staff, take a picture." Despite rules-of-engagement to the contrary, F-86 units frequently initiated combat over MiG bases in the Manchurian "sanctuary."[19] The hunting of MiGs in Manchuria would lead to many reels of gun camera footage being 'lost' if the reel revealed the pilot had violated Chinese airspace.

The needs of combat operation balanced against the need to maintain an adequate force structure in Western Europe led to the conversion of the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing from the F-80 to the F-86 in December 1951. Two fighter-bomber wings, the 8th and 18th, converted to the F-86F in the spring of 1953.[21] No. 2 Squadron, South African Air Force also distinguished itself flying F-86s in Korea as part of the 18 FBW.[22]

By the end of hostilities, F-86 pilots were credited with shooting down 792 MiGs for a loss of only 78 Sabres, a victory ratio of 10:1.[23] More recent research by Dorr, Lake and Thompson has claimed the actual ratio is closer to 2:1.[24]

The Soviets claimed to have downed over 600 Sabres,[25] together with the Chinese claims.[26]

A recent RAND report[27] made reference to "recent scholarship" of F-86 vs. MiG-15 combat over Korea and concluded that the actual kill:loss ratio for the F-86 was 1.8:1 overall, and likely 1.3:1 against MiGs flown by Soviet pilots; however, the report has been under fire for various misrepresentations.[28]

Of the 41 American pilots who earned the designation of ace during the Korean war, all but one flew the F-86 Sabre, the exception being a Navy F4U Corsair night fighter pilot.

Cold War

In addition to its distinguished service in Korea, USAF F-86s also served in various stateside and overseas roles throughout the early part of the Cold War. As newer Century Series fighters came on line, F-86s were transferred to Air National Guard (ANG) units or the air forces of allied nations. The last ANG F-86s continued in US service until the mid-1960s.

1958 Taiwan Strait Crisis

The Republic of China Air Force of Taiwan was one of the first recipients of surplus USAF Sabres. From December 1954 to June 1956, the ROC Air Force received 160 ex-USAF F-86F-1-NA through F-86F-30-NA fighters. By June 1958, the Nationalist Chinese had built up an impressive fighter force, with 320 F-86Fs and seven RF-86Fs having been delivered.

Sabres and MiGs were shortly to battle each other in the skies of Asia once again in the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis. In August 1958, the Chinese Communists of the People's Republic of China attempted to force the Nationalists off of the islands of Quemoy and Matsu by shelling and blockade. Nationalist F-86Fs flying CAP over the islands found themselves confronted by Communist MiG-15s and MiG-17s, and there were numerous dogfights.

During these battles, the Nationalist Sabres introduced a new element into aerial warfare. Under a secret effort designated Operation Black Magic, the US Navy had provided the ROC with the AIM-9 Sidewinder, its first infrared-homing air-to-air missile, which was just entering service with the United States. A small team from VMF-323, a Marine FJ-4 Fury squadron with later assistance from China Lake and North American Aviation, initially modified 20 of the F-86 Sabres to carry a pair of Sidewinders on underwing launch rails and instructed the ROC pilots in their use flying profiles with USAF F-100s simulating the MiG-17. The MiGs enjoyed an altitude advantage over the Sabres, as they had in Korea, and Communist Chinese MiGs routinely cruised over the Nationalist Sabres, only engaging when they had a favorable position. The Sidewinder took away that advantage and proved to be devastatingly effective against the MiGs.[29]

The combat introduction of the Sidewinder took place in a battle on 24 September 1958 when ROC Sabres succeeded in destroying 10 MiGs and scoring two probables without loss to themselves. In one month of air battles over Quemoy and Matsu, Nationalist pilots tallied a score of no less than 31 MiGs destroyed and eight probables, against a loss of two F-84Gs and no Sabres. The data comes from Nationalist Air Force filmed data.

Indo-Pakistani War of 1965

In 1954, Pakistan began receiving the first of a total of 120 F-86F Sabres. Many of these aircraft were the F-86F-35 from USAF stocks, but some were from the later F-86F-40-NA production block, made specifically for export. Many of the -35s were brought up to -40 standards before they were delivered to Pakistan, but a few remained -35s. The F-86 was operated by nine PAF squadrons at various times: Nos. 5, 11, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, and 26 Squadrons.

During the 22-day Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 the F-86 became the mainstay of the PAF, although the Sabre was no longer a world-class fighter, since fighters with Mach 2 performance were now in service. Many sources state the F-86 gave the PAF a technological advantage,[30] but others dispute this claim because the InAF fighters opposing it had greater performance.[31]

During the war, the United States barred sales of military equipment to Pakistan and the F-86 fleet was almost grounded due to lack of spare parts. Pakistan managed to procure around 90 Canadair CL-13 Sabre Mk 6 illegally from West Germany through Iran, these formed the backbone of the operations during the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War. The F-86 proved vulnerable to the diminutive Folland Gnat, which proved to be fast, nimble and hard to see. The IAF Gnats, given the nickname "Sabre Slayer," claimed to have downed seven PAF Sabres.[32][33][34]

Air to air combat

In the air-to-air combat of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, the PAF Sabres claimed to have shot down 15 IAF aircraft, comprising nine Hunters, four Vampires and two Gnats.[32] India, however, admitted a loss of 14 combat aircraft to the PAF's F-86s.[35] The F-86s of the PAF had the advantage of being armed with AIM-9B/GAR-8 Sidewinder missiles whereas none of its Indian adversaries had this capability. Despite this, the IAF claimed to have shot down four PAF Sabres in air-to-air combat.[33] This claim is disputed by the PAF who admit to having lost 7 F-86s Sabres during the whole 23 days but only three of them during air-to-air battles.[32]

The top Pakistani ace of the conflict was Wing Commander Mohammed Mahmood Alam, who ended the conflict claiming 11 kills. Pakistan Air Force F-86 Flying Ace Sqn Ldr Muhammad Mahmood Alam was officially credited with five kills in air-to-air combat,[36] three of them in less than a minute.[37] These five kills were all against Indian Air Force (IAF) Hawker Hunter Mk.56 fighters, which were export versions of the Hunter Mk.6 of the Royal Air Force.

Ground attack

The PAF Sabres performed well in ground attack with claims of destroying around 36 aircraft on the ground at Indian airfields at Halwara, Kalaikunda, Baghdogra, Srinagar and Pathankot.[32][38][39][40] India only acknowledges 22 aircraft lost on the ground to strikes partly attributed to the PAF's F-86s and its bomber B-57 Canberra.[35]

Pakistani F-86s were also used against advancing columns of the Indian army when No. 19 Squadron Sabres engaged the Indian Army using 5 in (127 mm) rockets along with their six .50 in (12.7 mm) M3 Browning machine guns. According to Pakistan reports, Indian armor bore the brunt of this particular attack at Wagah.[41] The Number 14 PAF Squadron earned the nickname "Tailchoppers" in PAF for their F-86 operations and actions during the 1965 war.[42]

Bangladesh Liberation War 1971

The Canadair Sabres (Mark 6), acquired from ex-Luftwaffe stocks via Iran, were the mainstay of the PAF's day fighter operations during the Bangladesh Liberation War 1971, and had the challenge of dealing with the threat from IAF. Despite having acquired newer fighter types such as the Mirage III and the Shenyang F-6, the Sabre Mark 6 (widely regarded as the best "dog-fighter" of its era[43]) along with the older PAF F-86Fs, were tasked with the majority of operations during the war, due to the small numbers of the Mirages and combat unreadiness of the Shenyang F-6.[13] In East Pakistan only one PAF F-86 squadron (14th Squadron) was deployed to face the formidable IAF Soviet MiG-21s and the Sukhoi SU-7 and the numerical superiority of the IAF. At the beginning of the war, PAF had eight squadrons of F-86 Sabres.[44]

Despite these challenges, the PAF F-86s performed well with Pakistani claims of downing 31 Indian aircraft in air-to-air combat including 17 Hawker Hunters, eight Sukhoi SU 7 "Fitters", one MiG 21, and three Gnats[45] while losing seven F-86s.[46] India however claims to have shot down 11 PAF Sabres for the loss of 11 combat aircraft to the PAF F-86s.[47] The IAF numerical superiority overwhelmed the sole East Pakistan Sabres squadron (and other military aircraft)[48][49] which were either shot down, or grounded by Pakistani Fratricide as they could not hold out, enabling complete Air superiority for the Indian Air Force.[50]

In the Battle of Boyra, the first notable air engagement over East Pakistan (Bangladesh), India claimed four Gnats downed three Sabres while Pakistan acknowledges only two Sabres were lost while one Gnat was shot down.[13]. As per official Pakistan accounts, 24 Sabres were lost in the war: 13 due to enemy action and 11 disabled by PAF forces to keep them out of enemy hands,[46] while 28 Sabres were lost per Indian accounts: 17 due to IAF action and 11 disabled by the PAF on the ground to keep them out of enemy hands.[51]. Five of these Sabres, however, were recovered in working condition and flown again by the Bangladesh Air Force.[51][52][53]

After this war, Pakistan slowly phased out its F-86 Sabres and replaced them with Chinese F-6 (Russian MiG-19 based) fighters. The last of the Sabres were withdrawn from service in PAF in 1980.[13] F-86 Sabres nevertheless remain a legend in Pakistan and are seen as a symbol of pride. They are now displayed in Pakistan Air Force Museum and in the cities to which their pilots lived.

Guinea Bissau

Based at AB2-Bissau/Bissalanca in 1961-1964, some F-86Fs were deployed in Guinea in 1961 where they were used in ground attack and close support operations. These aircraft formed “Detachment 52”, equipped with eight F-86Fs (serials: 5307, 5314, 5322, 5326, 5354, 5356, 5361 and 5362) of the Esquadra 51, based at the Base Aerea 5, in Monte Real, Portugal. In August 1962, 5314 overshot the runway during emergency landing with bombs still attached on underwing hardpoints and burned out. F-86 5322 was shot down by enemy ground fire on 31 May 1963; the pilot ejected safely and was recovered. Several other aircraft suffered combat damage, but were repaired.

In 1964, 16 F-86Fs based at Bissalanca returned to mainland due to U.S. pressure. They had flown 577 combat sorties, of which 430 were ground attack and close air support missions. During these operations, one FAP Sabre was shot down and another crashed.

Philippine Air Force

The Philippine Air Force first received the Sabres in the form of F-86Fs in 1957. Replacing the P-51 Mustang as the Philippine Air Force's primary interceptor. F-86s first operated from Basa Air Base, known infamously as the Nest of Vipers where the 5th Fighter Wing of the PAF was based. Later on, in 1960, the PAF acquired the F-86D as the first all weather interceptor of the PAF. The most notable use of the F-86 Sabres is in the Blue Diamonds (aerobatic team) aerobatic display team which operated 8 Sabres until the arrival of the newer, supersonic Northrop F-5. The F86s were subsequently phased out of service in the 1970s as the F-5 Freedom Fighter and F-8 Crusaders became the primary fighters and interceptors of the Philippine Air Force.

The most notable F-86 pilot of the PAF is Antonio Bautista who was a Blue Diamonds pilot and a decorated officer for his actions on January 11, 1974.

Soviet Sabre

During the Korean War, the Soviets were searching for an intact US F-86 Sabre for evaluation/study purposes. Their search was frustrated, largely due to the US military's policy of destroying their weapons and equipment once they had been disabled or abandoned; and in the case of US aircraft, USAF pilots destroyed most of their downed Sabres by strafing or bombing them. However, on one occasion an F-86 was downed in the tidal area of a beach and subsequently was submerged, preventing its destruction. The aircraft was ferried to Moscow and a new OKB was established to study the F-86, which later became part of the Sukhoi OKB. The F-86 studies contributed to the development of aircraft aluminum alloys (V-95 etc.).[54]

Variants

North American F-86

Wings Museum, Denver, CO.

- XF-86

- three prototypes, originally designated XP-86, North American model NA-140

- YF-86A

- this was the first prototype fitted with a General Electric J47 turbojet engine.

- F-86A

- 554 built, North American model NA-151 (F-86A-1 block and first order of A-5 block) and NA-161 (second F-86A-5 block)

- DF-86A

- A few F-86A conversions as drone directors

- RF-86A

- 11 F-86A conversions with three cameras for reconnaissance

- F-86B

- 188 ordered as upgraded A-model with wider fuselage and larger tires but delivered as F-86A-5, North American model NA-152

- F-86C

- original designation for the YF-93A, two built, 48-317 & 48-318,[55] order for 118 cancelled, North American model NA-157

- YF-86D

- prototype all-weather interceptor originally ordered as YF-95A, two built but designation changed to YF-86D, North American model NA-164

- F-86D

- Production interceptor originally designated F-95A, 2,506 built. See F-86D Sabre.

- F-86E

- Improved flight control system and an "all-flying tail" (This system changed to a full power-operated control with an "artificial feel" built into the aircraft's controls to give the pilot forces on the stick that were still conventional, but light enough for superior combat control. It improved high speed maneuverability); 456 built, North American model NA-170 (F-86E-1 and E-5 blocks), NA-172, essentially the F-86F airframe with the F-86E engine (F-86E-10 and E-15 blocks); 60 of these built by Canadair for USAF (F-86E-6)

- F-86E(M)

- Designation for ex-RAF Sabres diverted to other NATO air forces

- QF-86E

- Designation for surplus RCAF Sabre Mk. Vs modified to target drones

- F-86F

- Uprated engine and larger "6-3" wing without leading edge slats, 2,239 built; North American model NA-172 (F-86F-1 through F-15 blocks), NA-176 (F-86F-20 and -25 blocks), NA-191 (F-86F-30 and -35 blocks), NA-193 (F-86F-26 block), NA-202 (F-86F-35 block), NA-227 (first two orders of F-86F-40 blocks comprising 280 aircraft which reverted to leading edge wing slats of an improved design), NA-231 (70 in third F-40 block order), NA-238 (110 in fourth F-40 block order), and NA-256 (120 in final F-40 block order); 300 additional airframes in this series assembled by Mitsubishi in Japan for Japanese Air Self-Defense Force. Sabre Fs had much improved high speed agility, coupled with a higher landing speed of over 145 mph (233 km/h). The F-35 block had provisions for a new task: the nuclear tactical attack with one of the new small "nukes" ("second generation" nuclear ordnance). The F-40 had a new slatted wing, with a slight decrease of speed, but also a much better agility at high and low speed with a landing speed reduced to 124 mph (200 km/h). The USAF upgraded many of previous F versions to the F-40 standard.

- F-86F-2

- Designation for ten aircraft modified to carry the M39 cannon in place of the M3 .50 caliber machine gun "six-pack". Four F-86E and six F-86F were production-line aircraft modified in October 1952 with enlarged and strengthened gun bays, then flight tested at Edwards Air Force Base and the Air Proving Ground at Eglin Air Force Base in November. Eight were shipped to Japan in December, and seven forward-deployed to Kimpo Airfield as "Project GunVal" for a 16-week combat field trial in early 1953. Two were lost to engine compressor stalls after ingesting excessive propellent gases from the cannons.[56]

- QF-86F

- About 50 former JASDF F-86F airframes converted to drones for use as targets by the U.S. Navy

- RF-86F

- Some F-86F-30s converted with three cameras for reconnaissance; also eighteen JASDF aircraft similarly converted

- TF-86F

- Two F-86F converted to two-seat training configuration with lengthened fuselage and slatted wings under North American model NA-204

- YF-86H

- Extensively redesigned fighter-bomber model with deeper fuselage, uprated engine, longer wings and power-boosted tailplane, two built as North American model NA-187

- F-86H

- Production model, 473 built, with Low Altitude Bombing System (LABS) and provision for nuclear weapon, North American model NA-187 (F-86H-1 and H-5 blocks) and NA-203 (F-86H-10 block)

- QF-86H

- Target conversion of 29 airframes for use at United States Naval Weapons Center

- F-86J

- Single F-86A-5-NA, 49-1069, flown with Orenda turbojet under North American model NA-167 - same designation reserved for A-models flown with the Canadian engines but project not proceeded with

North American FJ Fury

- See: FJ Fury for production figures of U.S. Navy versions.

CAC Sabre (Australia)

Two types based on the US F-86F were built under licence by the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (CAC) in Australia, for the Royal Australian Air Force. as the CA-26 (one prototype) and CA-27 (production variant).

The CAC Sabres included a 60% fuselage redesign, to accommodate the Rolls-Royce Avon Mk 26 engine, which had roughly 50% more thrust than the J47, as well as 30 mm Aden cannons and AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles. As a consequence of its powerplant, the Australian-built Sabres are commonly referred to as the Avon Sabre. CAC manufactured 112 of these aircraft.

CA-27 marques:

- Mk 30: 21 built, wing slats, Avon 20 engine

- Mk 31: 21 built, 6-3 wing, Avon 20 engine

- Mk 32: 69 built, four wing pylons, F-86F fuel capacity, Avon 26 engine

The RAAF operated the CA-27 from 1956 to 1971.[57] Ex-RAAF Avon Sabres were operated by the Royal Malaysian Air Force (TUDM) between 1969 and 1972. From 1973 to 1975, 23 Avon Sabres were donated to the Indonesian Air Force (TNI-AU); five of these were ex-Malaysian aircraft.

Canadair Sabre

The F-86 was also manufactured by Canadair in Canada as the CL-13 Sabre to replace its de Havilland Vampires, with the following production models:

- Sabre Mk 1

- one built, prototype F-86A

- Sabre Mk 2

- 350 built, F-86E-type, 60 to USAF, three to RAF, 287 to RCAF

- Sabre Mk 3

- one built in Canada, test-bed for the Orenda jet engine

- Sabre Mk 4

- 438 built, production Mk 3, 10 to RCAF, 428 to RAF as Sabre F 4

- Sabre Mk 5

- 370 built, F-86F-type with Orenda engine, 295 to RCAF, 75 to Luftwaffe

- Sabre Mk 6

- 655 built, 390 to RCAF, 225 to Luftwaffe, six to Colombia and 34 to South Africa

Production summary

- NAA built a total of 6,297 F-86s and 1,115 FJs,

- Canadair built 1,815,

- Australian CAC built 112,

- Fiat built 221, and

- Mitsubishi built 300;

- for a total Sabre/Fury production of 9,860.

Production costs

| F-86A | F-86D | F-86E | F-86F | F-86H | F-86K | F-86L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program R&D cost | 4,707,802 | ||||||

| Airframe | 101,528 | 191,313 | 145,326 | 140,082 | 316,360 | 334,633 | |

| Engine | 52,971 | 75,036 | 39,990 | 44,664 | 214,612 | 71,474 | |

| Electronics | 7,576 | 7,058 | 6,358 | 5,649 | 6,831 | 10,354 | |

| Armament | 16,333 | 69,986 | 23,645 | 17,669 | 27,573 | 20,135 | |

| Ordnance | 419 | 4,138 | 3,047 | 17,117 | 4,761 | ||

| Flyaway cost | 178,408 | 343,839 | 219,457 | 211,111 | 582,493 | 441,357 | 343,839 |

| Maintenance cost per flying hour | 135 | 451 | 187 |

Note: The costs are in approximately 1950 United States dollars and have not been adjusted for inflation.[1]

Operators

- Source: Dorr[58]

Argentina: Argentine Air Force

Argentina: Argentine Air Force

- Acquired 28 F-86Fs, 26 September 1960, FAA s/n CA-101 through CA-128. The Sabres were already on reserve status at the time of the Falklands War but were reinstate to active service to bolster air defences against possible Chilean involvement. Finally retired in 1986.

.svg.png) Belgium: Belgian Air Force

Belgium: Belgian Air Force

- 5 F-86F Sabres delivered, no operational unit

Bolivia: Bolivian Air Force

Bolivia: Bolivian Air Force

- Acquired 10 F-86Fs from Venezuelan Air Force October 1973, assigned to Brigada Aerea 21, Grupo Aereo de Caza 32, they were reported to have finally been retired from service in 1994, making them the last Sabres on active front line service anywhere in the world.

Canada: Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF)

Canada: Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Colombia: Colombian Air Force

Colombia: Colombian Air Force

- Acquired two F-86Fs from Spanish Air Force (s/n 2027/2028), one USAF F-86F (s/n 51-13226) and other six Canadair Mk.6; assigned to Escuadron de Caza-Bombardero.

Ethiopia: Ethiopian Air Force

Ethiopia: Ethiopian Air Force

- Acquired 14 F-86Fs in 1960.[59]

Iran: Imperial Iranian Air Force

Iran: Imperial Iranian Air Force

- Acquired unknown number of F-86Fs[59]

- Acquired five F-86Fs[59]

.jpg)

Japan: Japanese Air Self-Defense Force

Japan: Japanese Air Self-Defense Force

- Acquired 180 U.S. F-86Fs, 1955-1957. Mitsubishi built 300 F-86Fs, 1956-1961, and were assigned to 10 fighter hikotai or squadrons, and their Blue Impulse Aerobatic Team. A total of 18 F-models were converted to reconnaissance version in 1962. Some aircraft were returned to the Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, California, as drones.

Norway: Royal Norwegian Air Force

Norway: Royal Norwegian Air Force

- Acquired 115 F-86Fs, 1957-1958; and assigned to seven Norwegian Squadrons, Nos. 331, 332, 334, 336, 337, 338 and 339.

- Acquired 102 U.S.-built F-86F-35-NA and F-86F-40-NAs (last of North American Aviation's production line, 1954-1960s.

Peru: Peruvian Air Force

Peru: Peruvian Air Force

- Acquired 26 U.S.-built F-86Fs in 1955, assigned to Escuadrón Aéreo 111, Grupo Aéreo No.11 at Talara air force base. Finally retired in 1979.

Philippines: Philippine Air Force

Philippines: Philippine Air Force

- Acquired 50 F-86Fs in 1957. Retired in early 1970s.

Portugal: Portugal Air Force

Portugal: Portugal Air Force

- Acquired 50 U.S.-built F-86Fs, 1958, including some from USAF's 531st Fighter Bomber Squadron, Chambley, Portugal.

-

- 201 Squadron "Falcões" (Falcons) (formerly designated as 50 Sqn. and later 51 Sqn., before being renamed in 1978), based at Air Base No. 5 (BA5), in Monte Real

- 52 Squadron "Galos" (Roosters), based at Air Base No. 5 (BA5), in Monte Real

Republic of China (Taiwan): Republic of China Air Force

Republic of China (Taiwan): Republic of China Air Force Saudi Arabia: Royal Saudi Air Force

Saudi Arabia: Royal Saudi Air Force

- Acquired 16 U.S.-built F-86Fs in 1958, and 3 Fs from Norway in 1966; and assigned to RSAF No. 7 Squadron at Dharhran.

South Africa: South African Air Force

South Africa: South African Air Force

- Acquired on loan 22 U.S.-built F-86F-30s during the Korean War and saw action with 2 Squadron SAAF.

South Korea: Republic of Korea Air Force

South Korea: Republic of Korea Air Force

- Acquired 122 U.S.-built F-86Fs and RF-86Fs, beginning 20 June 1955; and assigned to ROKAF 10th Wing.

-

- It also served with the ROKAF Black Eagles aerobatic team, until retired 1966.

- Acquired 270 U.S.-built F-86Fs, 1955-1958; designated C.5s and assigned to 5 wings: Ala de Caza 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6. Retired 1972.

Thailand: Royal Thai Air Force

Thailand: Royal Thai Air Force

- Acquired 40 U.S.-built F-86Fs, 1962; assigned to RTAF Squadrons, Nos. 12 (Ls), 13, and 43.

Tunisia: Tunisian Air Force

Tunisia: Tunisian Air Force

- Acquired 15 used U.S.-built F-86F in 1969.

- Acquired 12 U.S.-built F-86Fs.

Venezuela: Venezuelan Air Force

Venezuela: Venezuelan Air Force

- Acquired 30 U.S.-built F-86Fs, October 1955 - December 1960; and assigned to one group, Grupo Aerea De Caza No. 12, three other squadrons.

Yugoslavia: Yugoslav Air Force

Yugoslavia: Yugoslav Air Force

- Acquired 121 Canadair CL-13s and F-86Es, operating them in several fighter aviation regiments between 1956 and 1971.

Notable F-86 pilots

- Colonel Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin, USAF test pilot and Apollo 11 astronaut

- Captain Joseph C. McConnell (16 victories), USAF 51 FIW, who later died in a crash at Edwards Air Force Base testing the F-86H

- Major James Jabara (15 victories), USAF 4 FIW

- Captain Manuel "Pete" Fernandez, (14.5 victories), USAF 4 FIW

- Major George Davis (14 victories), USAF 4 FIW, awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously

- Brigadier General James Robinson Risner (eight victories), USAF awarded the Air Force Cross, later Vietnam War POW

- Colonel Francis S. "Gabby" Gabreski (six and one-half victories), USAF 51 FIW commander, top European U.S. ace in World War II

- Colonel Ralph "Hoot" Gibson (five victories), USAF 4 FIW

- Captain Iven Kincheloe (five victories) USAF 51 FIW, test pilot selected to fly the X-15

- Colonel Harrison R. Thyng (five victories), USAF 4 FIW commander

- Major John Glenn, a Marine Corps exchange pilot with the USAF 51 FIW

- Lieutenant Colonel Virgil Ivan "Gus" Grissom, astronaut in the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs, died in a fire during testing for the Apollo mission.

- Second Lieutenant Gene Kranz, NASA flight director for Gemini and Apollo and assistant flight director on Project Mercury- flew with 69th FBS in South Korea

- Colonel Walker "Bud" Mahurin, USAF 51st Fighter Group commander and World War II ace

- Squadron Leader Andy Mackenzie, DFC. RCAF WWII fighter ace (8.5 victories); taken POW when his F-86 was shot down while flying with the USAF 51 FIW in Korea in 1952.[60]

- Captain James Horowitz, USAF 4 FIW, novelist and author of The Hunters under the pen name James Salter

- Flying Officer Shaheed Waleed Ehsanul Karim, Pakistan Air Force, youngest Sabre pilot (first flew Sabres when he was eighteen).

- Air Commodore M. M. Alam, Pakistan Air Force, became a flying ace by shooting down 5 Indian Air Force fighters within one minute in 1965 war ,[36][37][61].

- Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Bautista of the Philippine Air Force received the Distinguished Conduct Star for his valor and bravery in providing close air support to ground forces. In his F86 he conducted five strafing passes at treetop level and two bombing runs. He died in an ensuing gun battle after his ejection.

- Captain James Kinchen, USAF Plattsburgh NY, SAC.

Survivors

Specifications (F-86F-40-NA)

Data from The North American Sabre[62]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 37 ft 1 in (11.4 m)

- Wingspan: 37 ft 0 in (11.3 m)

- Height: 14 ft 1 in (4.5 m)

- Wing area: 313.4 sq ft (29.11 m²)

- Empty weight: 11,125 lb (5,046 kg)

- Loaded weight: 15,198 lb (6,894 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 18,152 lb (8,234 kg)

- Powerplant: 1× General Electric J47-GE-27 turbojet, 5,910 lbf (maximum thrust at 7.950 rpm for five min) (26.3 kN)

- Fuel provisions Internal fuel load: 437 gallons (1,650 l), Drop tanks: 2 x 200 gallons (756 l) JP-4 fuel

Performance

- Maximum speed: 687 mph at sea level at 14,212 lb (6,447 kg) combat weight

also reported 678 mph (1,091 km/h) and 599 at 35,000 feet (11,000 m) at 15,352 pounds (6,960 kg). (597 knots, 1,105 km/h at 6446 m, 1,091 and 964 km/h at 6,960 m.) - Stall speed: 124 mph (power off) (108 kt, 200 km/h)

- Range: 1,525 mi, (1,753 NM, 2,454 km)

- Service ceiling: 49,600 ft at combat weight (15,100 m)

- Rate of climb: 9,000 ft/min at sea level (45.72 m/s)

- Wing loading: 49.4 lb/ft² (236.7 kg/m²)

- lift-to-drag: 15.1

- Thrust/weight: 0.38

- Landing ground roll: 2,330 ft, (710 m)

- Time to altitude: 5.2 min (clean) to 30,000 ft (9,100 m)

Armament

- Guns: 6 × 0.50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns (1,602 rounds in total)

- Rockets: variety of rocket launchers; e.g: 2 × Matra rocket pods with 18× SNEB 68 mm rockets each

- Missiles: 2× AIM-9 Sidewinders

- Bombs: 5,300 lb (2,400 kg) of payload on four external hardpoints, bombs are usually mounted on outer two pylons as the inner pairs are wet-plumbed pylons for 2 × 200 gallons drop tanks to give the Sabre a useful range. A wide variety of bombs can be carried (max standard loadout being 2 × 1,000 lb bombs plus 2 drop tanks), napalm bomb canisters and can include a tactical nuclear weapon.

See also

- Tactical Air Command

- Semi-Automatic Ground Environment

Related development

- FJ-1 Fury

- F-86D Sabre

- Canadair Sabre

- CAC Sabre

- FJ-2/-3 Fury

- FJ-4 Fury

- North American YF-93

- Fuji T-1

- F-100 Super Sabre

Comparable aircraft

- F-9 Cougar

- FMA IAe 33 Pulqui II

- F-84F Thunderstreak

- Dassault Mystère

- Focke-Wulf Ta 183

- Hawker Hunter

- Lavochkin La-15

- Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15

- Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17

- Saab 29 Tunnan

Related lists

- List of military aircraft of the United States

- List of fighter aircraft

- List of airshow accidents

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Knaack 1978

- ↑ Winchester 2006, p. 184.

- ↑ The FJ-1 Fury

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Aviation History On-line Museum

- ↑ Willy Radinger and Schick 1996, p. 15.

- ↑ Willy and Schick 1996, p. 32.

- ↑ North American F-86 Sabre (Day-Fighter A, E and F Models)

- ↑ Planes of Perrin, North American F-86L "Dog Sabre"

- ↑ The History of North American Small Gas Turbine Aircraft Engines By Richard A. Leyes, William A. Fleming

- ↑ F-86E Through F-86L

- ↑ North American F-86H Sabre (Fighter-Bomber)

- ↑ Joos 1971, p. 3. Quote: "The Canadair Sabre Mk 6 was the last variant and considered to be the 'best' production Sabre ever built."

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Pakistan Air Force - The Canadair Sabre Goes to War

- ↑ History of the F-86 Sabre Jet on Boeing's website

- ↑ Wagner 1963, p. 17.

- ↑ Aeronautics and Astronautics Chronology, 1945-1949

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Sabre: The F-86 in Korea

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Fact Sheet: The United States Air Force in Korea

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Bud" Mahurin

- ↑ Lt.Col. George Andrew Davis

- ↑ USAF Organizations in Korea, Fighter-Interceptor 4th Fighter-Interceptor Wing

- ↑ The History of No 2 Squadron, SAAF, in the Korean War

- ↑ Thompson, Warren E. and McLaren, David R. MiG Alley: Sabres Vs. MiGs Over Korea. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2002. ISBN 1-58007-058-2.

- ↑ Dorr, Robert F., Jon Lake and Warren E. Thompson. Korean War Aces. London: Osprey Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1-85532-501-2.

- ↑ Russian Claims from the Korean War 1950-53

- ↑ Zhang, Xiaoming. Red Wings over the Yalu: China, the Soviet Union, and the Air War in Korea. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 2002. ISBN 1-58544-201-1.

- ↑ Stillion, John and Scott Perdue. "Air Combat Past, Present and Future." Project Air Force. Rand, August 2008. Retrieved: 11 March 2009.

- ↑ Stillion, John and Scott Perdue. (August 2008) "Air Combat, Past Present and Future." Project Air Force. Rand, August 2008. Retrieved: 11 March 2009.

- ↑ 323 Death Rattlers

- ↑ Pakistan's Defence Journal

- ↑ "Pakistan's Air Power", Flight International, issue published 5 May 1984 (page 1208). Can be viewed at FlightGlobal.com archives, URL: http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1984/1984%20-%200797.html?search=F-86%20Pakistan Retrieved: 22 October 2009

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 Claims and Counter Claims- PakDef.Info

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 IAF Kills in 1965

- ↑ Folland FO-141 Gnat Note: The Pakistan Air Force disputes this claim and accepts the loss of only three F-86 Sabres at the hands of the Gnats.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 1965 Losses

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Pakistan Air Force official website

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Alam’s Speed-shooting Classic

- ↑ Defence Journal: A Hero Fades Away Feb-Mar. 1999

- ↑ Defence Journal: Tail Choppers - Birth of a Legend, December 1998

- ↑ Defence Journal: Devastation of Pathankot, September 2000

- ↑ Devastation of Pathankot

- ↑ Tailchoppers

- ↑ Canadair CL-13 Sabre - Royal Canadian Air Force

- ↑ ""India and Pakistan: Over the Edge." TIME, 13 December 1971. Retrieved: 11 March 2009.

- ↑ PAF Kills and claims in 1971 - Pakdef.info

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 PAF Losses in 1971 Pakdef.info

- ↑ IAF Losses in 1971 - Bharat Rakshak.com

- ↑ Military losses in the 1971 Indo-Pakistani war

- ↑ Bangladesh, The Liberation War

- ↑ Singh et al. 2004, p. 30.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Aircraft Losses in Pakistan -1971 War

- ↑ Bangladesh Air Force History

- ↑ Virtual Bangladesh:Defense:Airforce

- ↑ Soviet Sabre

- ↑ North American YF-93A Fact Sheet

- ↑ Thompson, Warren E., and McLaren, David R. (2002). MiG Alley: Sabres vs. MiGs Over Korea. North Branch, MN: Specialty Press, ISBN 1-58007-058-2, pp. 139-155, researched by North American tech rep John L. Henderson. The aircraft were F-86E-10's 51-2303, -2819, -2826, and -2836; and F-86F-1's 51-2855, -2862, -2867, -2868, -2884, and -2900.

- ↑ RAAF Museum page on Sabre

- ↑ Dorr 1993, pp. 65–96.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Baugher's: F-86 Foreign Service

- ↑ S/L ANDY MacKENZIE, RCAF (Ret). Sabre Jet Classics Volume 10 Number 1 Winter 2003

- ↑ Pushpindar, Singh. Fiza ya, Psyche of the Pakistan Air Force. New Delhi: Himalayan Books, 1991. ISBN 81-7002-038-7.

- ↑ Wagner 1963, p. 145.

Bibliography

- Allward, Maurice. F-86 Sabre. London: Ian Allen, 1978. ISBN 0-71100-860-4.

- Curtis, Duncan. North American F-86 Sabre. Ramsbury, UK: Crowood, 2000. ISBN 1-86126-358-9.

- Dorr, Robert F.F-86 Sabre Jet: History of the Sabre and FJ Fury. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International Publishers, 1993. ISBN 0-87938-748-3.

- Joos, Gerhard W. Canadair Sabre Mk 1-6, Commonwealth Sabre Mk 30-32 in RCAF, RAF, RAAF, SAAF, Luftwaffe & Foreign Service. Kent, UK: Osprey Publications Limited, 1971. ISBN 0-85045-024-1.

- Käsmann, Ferdinand C.W. Die schnellsten Jets der Welt: Weltrekord- Flugzeuge (in German). Oberhaching, Germany: Aviatic Verlag-GmbH, 1994. ISBN 3-925505-26-1.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size. Encyclopedia of US Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems, Volume 1, Post-World War Two Fighters, 1945-1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1978. ISBN 0-912799-59-5.

- Radinger, Willy and Walter Schick. Me 262: Entwicklung und Erprobung des ertsen einsatzfähigen Düsenjäger der Welt, Messerschmitt Stiftung (in German). Berlin: Avantic Verlag GmbH, 1996. ISBN 3-925505-21-0.

- Singh, Sarina et al. Pakistan & the Karakoram Highway. London: Lonely Planet Publications, 2004. ISBN 0-86442-709-3.

- Swanborough, F. Gordon. United States Military Aircraft Since 1909. London: Putnam, 1963. ISBN 0-87474-880-1.

- United States Air Force Museum booklet. Dayton, Ohio: Air Force Museum Foundation, Wright-Patterson, 1975.

- Wagner, Ray. American Combat Planes - Second Edition. New York: Doubleday and Company, 1968. ISBN 0-370-00094-3.

- Wagner, Ray. The North American Sabre. London: Macdonald, 1963. No ISBN.

- Werrell, Kenneth P. Sabres Over MiG Alley. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2005. ISBN 1-59114-933-9.

- Westrum, Ron. Sidewinder. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1999. ISBN 1-55750-951-4.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. Military Aircraft of the Cold War (The Aviation Factfile). London: Grange Books plc, 2006. ISBN 1-84013-929-3.

External links

- F-86 Sabre Pilots Association

- Globalsecurity.org profile of the F-86 Sabre

- Four part series about the F-86 Sabre – Extended F-86 Sabre article set

- Warbird Alley: F-86 Sabre page – Information about F-86s still flying today

- Sabre site

- F-86 in Joe Baugher's U.S. aircraft site

- Aviation Museums of the World

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||